They lined up early today. I can see them, though right now I’m a thousand miles away. An eagerness shines in their eyes as they clutch their purses and wallets and try to peer in the windows, lured by the siren call of Craigslist and the newspaper ad, though a privileged few were on the private list of the organizer. Estate Sale Time.

Today is the day when most of the material possessions that my parents amassed in their 60+ years together are being offered for sale. The four of us kids have already gone through and selected the few items that we couldn’t live without (and that would fit in our respective houses), but there was still so much left over. Until today.

I do not want to be there. I can’t bear hearing the sad groan from the table that has been in our family for as long as I can remember, or the surprised look of betrayal from the figurine that has sat on the entryway shelf for just as long, as they are hoisted by unfamiliar hands and loaded into a strange minivan or truck to be carted off by a gleeful bargain hunter who has no sense of the road we have traveled together. So, I left Corpus Christi three days ago, turning over the keys to the energetic silver-haired woman who, with her kind assistants, is running the sale for us.

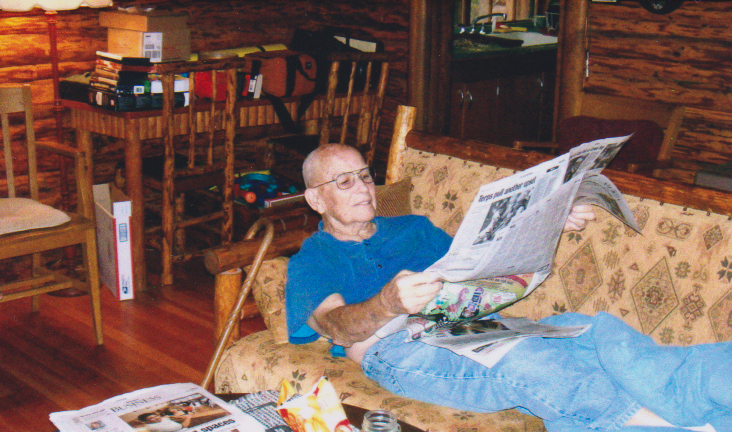

I spent a final five days in the house before that. I slept in my mom’s bed, took naps on the uber-comfortable sofa that was my frequent landing spot when I visited home, wandered barefoot on the cool Saltillo tile that runs throughout the house. I admired the dark varnished wood of all the built-in shelves, marveled at the endless walk-in closets—seven of them! Mom’s pride and joy—and smiled affectionately as I surveyed the end of the living room that we sometimes called “The Helm.” This was the Command Center from which my parents, strapped into their recliners with matching remotes and twin telephones close at hand, spent their days—monitoring world affairs, coordinating medical appointments, checking on the troops, barking out crossword clues, and doing the daily Jumble. I continued my roaming, taking in all the desks, shelves, pictures, chairs, coffee tables, knickknacks, and piles of books that have furnished an entire wing of my life.

I’ve had a growing awareness over the past couple of visits that looking at certain objects instantly conjures a whole host of associations, a history, a feeling of strong familiarity. I belong here. That dresser—that’s a Kisling dresser. As I’ve awaited the advent of this day, I’ve wondered if there are certain aspects of myself and my history that are only accessible through these portals. Was I, in a sense, saying good-bye to parts of myself that I would no longer have means to reach?

Maybe so. I remember in college being weirded out by an intro to psychology class (I only lasted the first week). The bearded professor, a noted phenomenologist, put to us the idea that, if certain memories surface only in the presence of certain places and objects, might it perhaps be more appropriate to say that those memories are actually contained in the places and things, rather than inside of us?

I get it now.

Of course, even if that’s true, I don’t know that it’s a bad thing. It’s just A Thing, which currently feels quite strange in its newness. To the extent that such shedding allows me to detach from material possessions and make room for new adventures and new memories, well, that can be quite a useful thing. Salvific, even. And I’m aware that this concern of mine is absolutely a First World problem. We as a family are letting go of Way More Stuff than most people on the planet ever accumulate in their entire lives. I in particular have had the luxury of more time to linger and say good-bye than many people get in similar situations. But, in spite of this knowledge of the privilege of my position, there have been tears—cleansing tears—and I have welcomed them.

One day, during this last visit, I sat at the dining table in my usual spot and had a conversation with Mom and Dad (well, with their chairs, anyway—which I pulled out slightly to give them room to sit down in the event they felt like stopping by). In our discussion, we acknowledged that those meal-times were not always easy; there was sometimes an edge of impatience, particularly in later years as Mom watched my increasingly infirm Dad fumble with his food, or as we raced through dinner to get done in time to tune in for the Sacred Weather Report. But they were our meal-times. They were as imperfect as the sum of their parts—us—but they are also precious to me because of that.

When I would visit my parents, I most often drove instead of flying. The night before I would leave for the return trek, I would give my folks an estimated departure time sometime the next morning. These estimates proved to be about as reliable as my predicted arrival times. The appointed hour would come and roll by, and I would still be puttering around, loading the car, making last sweeps for forgotten items. Finally, at some point, my Dad would call out from his armchair with mild exasperation, “Okay, Buddy. It’s time to hit the road.”

This past Monday morning, before heading to the airport (I had flown this time), I wandered through the house, taking it all in, watching the clock, occasionally checking UBER on my iPhone, wondering when I should press the button to summon the driver. And then, suddenly, I heard it—clearly, one more time: “Okay, Buddy. It’s time.”

I knew he was right. So, I placed my hand gently over my heart, allowed myself one last lingering glance, turned the lock on the inside of the knob, and with a whispered “Thank you” for all that it had meant to me, I stepped out and closed the door behind me.